Introduction

After almost 50 auctions between June, 2018, and April, 2025, involving some 6,800 coins, the Stack’s Bowers Galleries (SBG) Fairmont sales have officially ended. Among these auctions have been 29 sales that included at least 50 coins with the “Fairmont Collection” pedigree. There have been 13 Fairmont-only sessions, including the initial June, 2018, sale of double eagles, the August, 2020, sale of half eagles, and 11 “named-set” auctions that included half eagles, eagles, and double eagles. A single stray $3 coin and one $5 Territorial were sold. No gold dollars or quarter eagles have appeared among the Fairmont coins.

I wrote the first of this series of articles in late 2023, midway through the named-set Fairmont auctions, and followed it with eight more. It now seems appropriate that I write a final piece updating and summarizing these articles.

This recapitulation will broadly follow the sequence of the series. For the most part, I will not repeat in lengthy detail material that has appeared previously; rather, I will simply provide highlights and pointers.

The Pedigreed Fairmonts

At the present time, the Fairmont Collection comprises about 8,300 US gold coins, graded by the Professional Coin Grading Service (PCGS) and bearing “The Fairmont Collection” pedigree on their holders. Accordingly, I refer to these as the “pedigreed” Fairmont coins. By searching SBG auction records, the PCGS “Cert Verification” database, plus several dealer inventories, I have built a database for the pedigreed Fairmont coins that I believe to be more-or-less complete.

My list of pedigreed Fairmonts continues to grow, slowly. For example, in early May, JM Bullion, a corporate affiliate of SBG, offered for sale some pedigreed Fairmont Liberty T3 $20s, and, in consequence, I added 19 pedigreed Fairmont double eagles to my database. However, for this article, I decided to freeze the numbers as of early April, 2025 – a few more coins do not change things much.

In any case, unless SBG decides to release an inventory of the Fairmont coins, we will never know for sure exactly how many there are. The numbers that I provide here are perhaps best regarded as lower bounds – as the above example illustrates, it is almost certain that I have not yet found the records for all the pedigreed Fairmonts, and I probably never will. That said, the table below presents the demographics for the pedigreed Fairmonts, excluding the $3 piece and the $5 Territorial, as I knew them in early April.

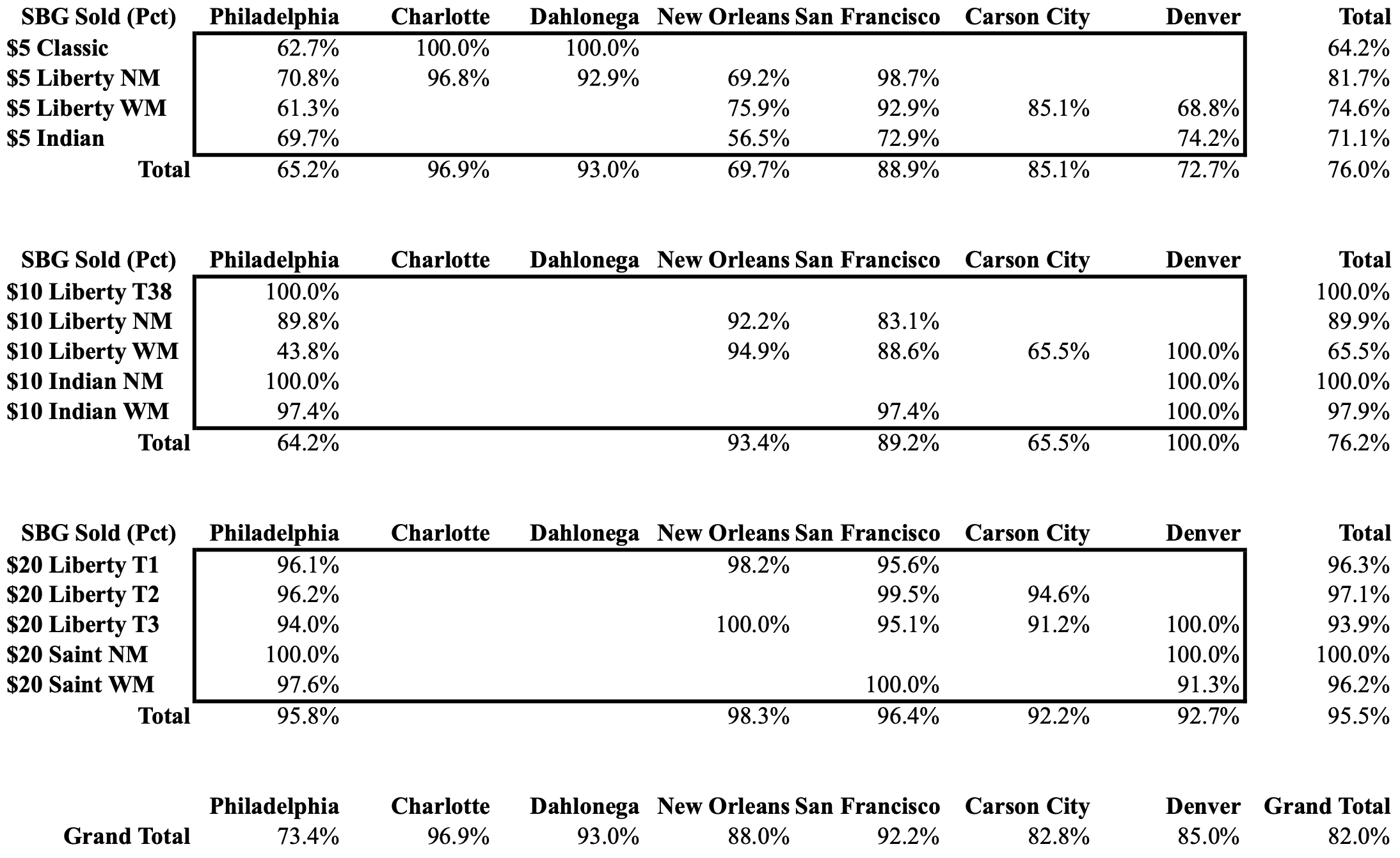

As of April, 2025, 82% of the pedigreed Fairmonts have been sold in SBG auctions. The table below presents these numbers, expressed as percentages of the known totals.

Obviously, a substantial number of pedigreed Fairmonts, perhaps about 1,500 coins, have not been sold in SBG’s auctions. Some of these coins have been distributed outside the auctions through dealers and marketers such as JM Bullion. Doug has obtained and sold some. Some have been sold privately. Even Heritage has auctioned at least one pedigreed Fairmont as a first-time sale. However, the evidence currently suggests that these sales do not account for most of the 1,500 coins, and I suspect that many of them remain unsold today.

The 1,500 coins are not evenly distributed across the three denominations. Relatively few are double eagles. Among the half eagles and the eagles, a significant number comprise just two issues, the remainders from 300 1901 $5s and 300 1901 $10s that were submitted to PCGS, perhaps in early 2018, almost all of which were graded MS-63. A few of these 600 coins have entered the marketplace, but I think most of them have not.

Among the half eagles, it appears that essentially all the Classic Head coins in the Fairmont hoard were graded with the pedigree. It also appears that essentially all the coins for a few of the common dates among the No-Motto Liberties, notably 1844-O, 1845, 1846 (large date), and 1848, were also graded with the pedigree. Somewhat more than 200 of these coins, generally those with lower grades, have never passed through the SBG auctions, and are included among the 1,500 coins.

There are about 60 1892-CC pedigreed Fairmont $10s among the 1,500 coins.

The remainder are scattered across the spectrum. Most are relatively common dates, although there are a few from the scarcer issues. I am aware of no rarities among the 1,500 coins.

Despite the word “collection,” the Fairmont Collection is not a purpose-built collection in the usual sense of the word – rather, it is part of a hoard. It is now evident that the pedigreed Fairmonts, as defined above, comprise only about 2% of a much larger parent population of perhaps 400,000 coins, encompassing the best coins from this parent population in terms of both rarity and condition.

Because the pedigreed Fairmonts are the choicest from the hoard, it is not surprising that a relatively large fraction of them have received CAC approval. The table below presents the numbers, expressed as percentages of the 6,800 pedigreed Fairmonts sold in the SBG auctions, for which SBG has provided images of the coins in their holders. Of course, is only by inspecting the holder that one can determine for certain whether or not a given coin has been awarded a CAC sticker; interrogating the CAC database by PCGS Cert Number is insufficient.

What strikes my eye in scanning this table is that CAC was noticeably harder on the double eagles than the half eagles and eagles, and was also picky about the $5 Indians and the San Francisco $10 Indians, relative to the Liberties. In contrast, there was little distinction between the $20 Saints and the Liberties. Whether this is telling us something about CAC’s approval standards, or the pedigreed Fairmonts, or perhaps a bit of both, is not a question I can answer.

One of the surprises of the Fairmont sales has been the appearance of a number of proofs, often lightly circulated. By my count, there were 53 of these (as identified by PCGS – SBG argues that there were a couple more) – 39 half eagles (38 Liberty + 1 Indian), 10 eagles (all Liberties), and 4 double eagles (also all Liberties). Evidently, the mint did not simply destroy unsold proofs, but rather released at least some of them into circulation.

The Non-Pedigreed Fairmonts

As mentioned previously, it is now evident that the pedigreed Fairmonts comprise only about 2% of a much larger parent population of perhaps 400,000 coins. The vast majority of the coins in this parent population – probably about 90% – have been graded by PCGS without the Fairmont pedigree on their holders. I will, accordingly, refer to them as the “non-pedigreed” Fairmont coins.

I have developed a method for estimating the total number of PCGS-graded Fairmont coins (i.e., pedigreed + non-pedigreed, combined) for any date/mint variety by analyzing time series, which I have constructed from historical records of the PCGS Population Report database. These time series track the cumulative counts of US gold coins graded by PCGS for every date/mint variety, starting in late 2017 and ending at the current time, with a two-month cadence. More information about the construction and analysis of these time series may be found in the second and sixth articles of this series.

This procedure allows me to estimate numbers for the more common varieties of gold coins in the Fairmont hoard without reference to the database. Some of these common varieties are represented by hundreds, or even thousands, of coins in the Fairmont hoard, among which the pedigreed Fairmonts typically number no more than 20-30 coins.

Although I believe the estimates obtained from my time series reference Fairmont coins (mostly the non-pedigreed Fairmonts), it is possible that some do not. For example, the time series for the 1857 San Francisco eagles and double eagles (and a year or two prior) include coins from the S.S. Central America treasure that were graded by PCGS in 2018. It is, of course, possible to correct the estimates for known instance like this one, but there may be others of which I remain unaware.

Furthermore, the best I can obtain from any individual time series is an estimate for the total number of Fairmont coins, pedigreed and non-pedigreed combined, that have been graded by PCGS between late 2017 and the present, and not an exact number. Like any estimate, it is inherently imprecise. I believe this uncertainly to be about ±10 coins, perhaps a bit fewer for the scarcer issues, and more for the common dates, for which literally thousands of (mainly non-pedigreed) Fairmont coins sometimes exist.

Like my database of pedigreed Fairmonts, my estimates for the total number of Fairmonts continues to grow, slowly. For example, after I froze my numbers in early April, the time series for 1913 Indian half eagles graded by PCGS abruptly jumped by 4,179 coins (32%). This event had all the hallmarks of a batch of non-pedigreed Fairmonts passing through PCGS grading. Although jumps of this size in the time series are no longer common, they still occur occasionally, and probably will continue to do so. Frankly, I do not expect SBG to ring a bell to announce the end of Fairmont grading.

This all said, the table below presents the demographics for the entire Fairmont hoard as I knew them in early April, when I froze the numbers.

The numbers are astonishing. Evidently even the professionals are amazed: to quote what Brian Kendrella wrote in his preface to the February, 2025, Riviera Set sale (the final named-set Fairmont auction):

“… the Fairmont Collection was the largest accumulation of United States gold coins to ever come to market … Generations of numismatic scholarship have been altered, and these sales have forced the revision of survival estimates for many different dates, especially among branch mint Liberty Head gold coins.”

According to the table, Philadelphia coins make up over 76% of the total; coins from San Francisco account for less than 16%. The ratio is about 4.86:1. However, the original mintage ratio is considerably smaller, about 1.4:1. I believe this is telling us that the Fairmont hoard was originally assembled on the East Coast; had it been formed on the West Coast, it seems plausible that the imbalance between Philadelphia coins and San Francisco coins, relative to mintage, would be considerably smaller. I will subsequently return to this point in more detail.

I believe that many of the non-pedigreed Fairmonts remain unsold at the present time.

The Ungraded Fairmonts

It seems likely that perhaps 5% – 10% of the coins from the Fairmont parent population have never been submitted to PCGS for grading, presumably because they are badly worn or damaged, and were therefore deemed not worth the expense. I refer to these shadowy coins as the “ungraded” Fairmonts.

In one of the Sherlock Holmes stories, the fact that a dog did not bark during the night when a crime was committed became an important clue to solving the case. Likewise, in studying the Fairmont coins, I have realized that it is useful to consider what seems to be missing, as well as what is present. In this case, what seems to be missing are the low-grade coins at the bottom of the grade distribution – not totally absent, to be sure, but noticeably so.

The explanation is probably fairly simple: the coins are not missing, but rather they simply have never been graded. Low-grade Fairmonts exist, and have appeared occasionally in the SBG auctions. There just have not been very many of them. However, those that have shown up also tend to be from scarcer issues.

Among these coins, the single 1870-CC eagle among the Fairmonts that graded PCGS G-6 stands out like the proverbial sore thumb. It seems inconceivable that the only Carson City coin in the Fairmont hoard with a grade this low would also be a leading rarity – rather, I suspect, the only 1870-CC eagle in the Fairmont hoard also happened to be a low-grade coin. Surely, if there is one low-grade 1870-CC Fairmont eagle, there must also be dozens, or even hundreds, of similarly low-grade Fairmonts for the more common issues.

Accordingly, one approach to estimating the number of ungraded Fairmonts is to compare the low end of the grade distribution for Fairmonts with the corresponding tail of the distribution for all PCGS-graded coins, as I did in the third article in this series. The numbers are uncomfortably soft, but various analyses consistently suggest that the missing low-grade tail of the Fairmont distribution is perhaps 5% – 10% of the total.

There is, in fact, little incentive to have worn common-date gold coins graded, Fairmont or otherwise – their numismatic value exceeds their bullion value only slightly, and the difference is, oftentimes, comparable to the grading cost. Indeed, I think it is likely that some ungraded Fairmont coins have been consigned directly to SBG’s Precious Metals (i.e., bullion) sales during the past several years. For example, in mid-2020, SBG sold several hundred ungraded common-date half eagles in their Precious Metals sales, including 115 moderately-worn 1895 $5 coins. About the same time in mid-2020, my time series show that PCGS graded almost 1,700 non-pedigreed Fairmont 1895 $5 coins. It is tempting to connect the two events: the better coins were sent to PCGS for grading, and the numismatically less attractive coins (about 7% of the total) were consigned directly to the bullion sales.

However, I tend to discount stories that truly large numbers of badly worn and/or damaged Fairmont coins have been culled and (perhaps) melted. The reason is that, if anything, the Fairmont hoard seems to be characterized by too few examples of rarities, relative to the more common dates. This feature would disappear in the face of wholesale culling of common-date coins.

A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words …

In the seventh article in this series, I described a simple two-parameter model, using mintage and attrition over time as independent variables, which I used for modelling the observed distribution of the Fairmont No-Motto $5s (i.e., the Classic Head and No-Motto Liberty half eagles issued from 1834 to 1866-S). The model worked surprisingly well. In this section, I will extend that model to the entire universe of Fairmont coins.

At first blush, the notion of using mintage numbers to predict survival rates for the Fairmont coins may seem naively absurd: everyone knows that the numbers of present-day survivors are but tiny fractions of the original mintages. However, even though the loss rates were very high, mintage numbers still matter. Indeed, the most important predictor for the number of Fairmont coins for any date/mint variety is mintage: high-mintage issues strongly tend to be represented by relatively numerous Fairmont coins, and low-mintage issues by fewer.

Even so, raw mintage numbers are not very good quantitative predictors for survival. One reason is attrition – as gold coins circulated, they became worn or damaged. Gold coins were legal-tender money, but only if they were full-weight, and a worn coin is underweight. Such coins were, accordingly, removed from circulation, and their gold content was re-coined into current, full-weight coins. Older coins, being exposed longer to wear, were systematically less likely to survive this removal process.

Besides attrition through wear, there were several other ways gold coins left the domestic US circulating coin stock: some (indeed, ultimately most) were lost, hidden in hoards, exported, or recalled & melted. However, to the extent that such events affected the pre-Civil War gold coin population (and they certainly did), they probably affected all the date/mint varieties more-or-less in proportion to mintage, which is why the model works as well as it does.

For the model, I assume that the number of survivors for each issue in the Fairmont hoard is proportional to the original mintage, and then remove that dependence from the data by multiplying the estimated numbers of Fairmont coins for each variety by the quantity: (1,000,000 / mintage). This produces a parameter (pieces per million, or PPM) that equals the number of Fairmont coins that would exist for each variety as if a million coins had been minted for each, everything else being equal. This rescaling doesn’t really change anything – it just makes the numbers easier to deal with.

To model attrition, I adopted a specific attrition law known as exponential decay, which stipulates that a constant fraction (5%, for example) of the surviving members of an initial population is lost during each successive time step (each year, for example). One well-known example of exponential decay found in nature is radioactive decay. Carbon-14 dating is an example of its use.

An important feature of the model is that, in the ideal case, it predicts that the PPM should be exactly 1,000,000 for the year in which the Fairmont hoard was assembled, presumably 1932, and decrease steadily, year-by-year, for earlier dates.

The figure below shows the result for the Fairmont half eagles. The coins from each of the seven mints are color-coded, and I selected colors that make the coins from Charlotte, Dahlonega, and Carson City relatively easy to spot. I pinned the straight trend line to a value of 1,000,000 in 1932, and simply eye-balled the left end to more-or-less follow the data. The fact that the trend line rises from left to right means that attrition is present, as expected. If the input data were perfectly represented by the model, implying that attrition were the only operative loss mechanism, the input points would all lie along the trend line.

Visual inspection of the figure shows that the data points for the Fairmont $5s from Philadelphia, Charlotte, Dahlonega, and New Orleans before the mid-1870s all cluster fairly nicely around the trend line, albeit with some scatter, which is expected because statistical variation is present. In other words, the attrition model describes the distribution of these Fairmont coins reasonably well.

For half eagles issued after about 1875, however, the data points strongly tend to fall significantly below the trend line, which means there are fewer of these coins in the Fairmont hoard than the model predicts. In particular, the Fairmont half eagles from Carson City and San Francisco show this behavior, and closer inspection shows that San Francisco coins from before 1875 also show this behavior.

I believe two factors are responsible for this.

The more important of these was the massive export of US gold coins that began in the late 1870s, and continued through 1932. Often, the export involved bags of newly- or recently-minted gold coins, usually the high-value $10 and $20 pieces, being sent to Europe, where they remained for decades before starting to find their way back to the US in the 1960s, sometimes in large numbers. In some cases, sizeable fractions of entire mintages were exported to Europe rather than released into domestic circulation, which explains how it is that large numbers of high-condition (albeit often heavily bag-marked) survivors are now known for certain date/mint varieties, especially in the $10 and $20 series.

This export activity dramatically affected the distributional characteristics of the gold coins remaining in the US in 1932, from which the Fairmont hoard was assembled. In terms of the model, the mintage numbers after about 1875 need to be corrected (i.e., reduced) to account for exports, but this is, in general, impossible.

At a more fundamental level, what this is saying is that mintage numbers are an imperfect proxy for what the attrition model actually requires, which are the numbers of gold coins that actually entered domestic US circulation and then stayed there for several years. Before the mid-1870s, these were essentially the entire mintages.

After that time, however, circulation became increasingly disconnected from mintage through export and, in the 1920s & 1930s, by the fact that some issues (such as the 1929 $5s) were largely withheld from circulation before the gold recall of 1933, and then melted. In other words, after the mid-1870s, mintages tend to overstate circulation, and do so very unevenly. Consequently, the PPM data points after the mid-1870s, calculated from mintages, tend to fall below the trend line, an especially dramatic case being the 1929 half eagles.

The second factor is the likelihood that the Fairmont hoard was probably assembled on the East Coast, perhaps in a New York City bank, and coins from Carson City and San Francisco were systematically under-represented among the available coins. The fact that the San Francisco issues are everywhere deficient, relative to Philadelphia coins, is fairly strong evidence for this.

The following two figures show the models for the Fairmont eagles and double eagles. The features are similar to those observed among the half eagles, with two notable differences: for the Fairmont double eagles, the coins from Carson City do not appear to be deficient, relative to Philadelphia coins, and neither are the early-date double eagles from San Francisco. Something remains unexplained.

The Fairmont Auctions

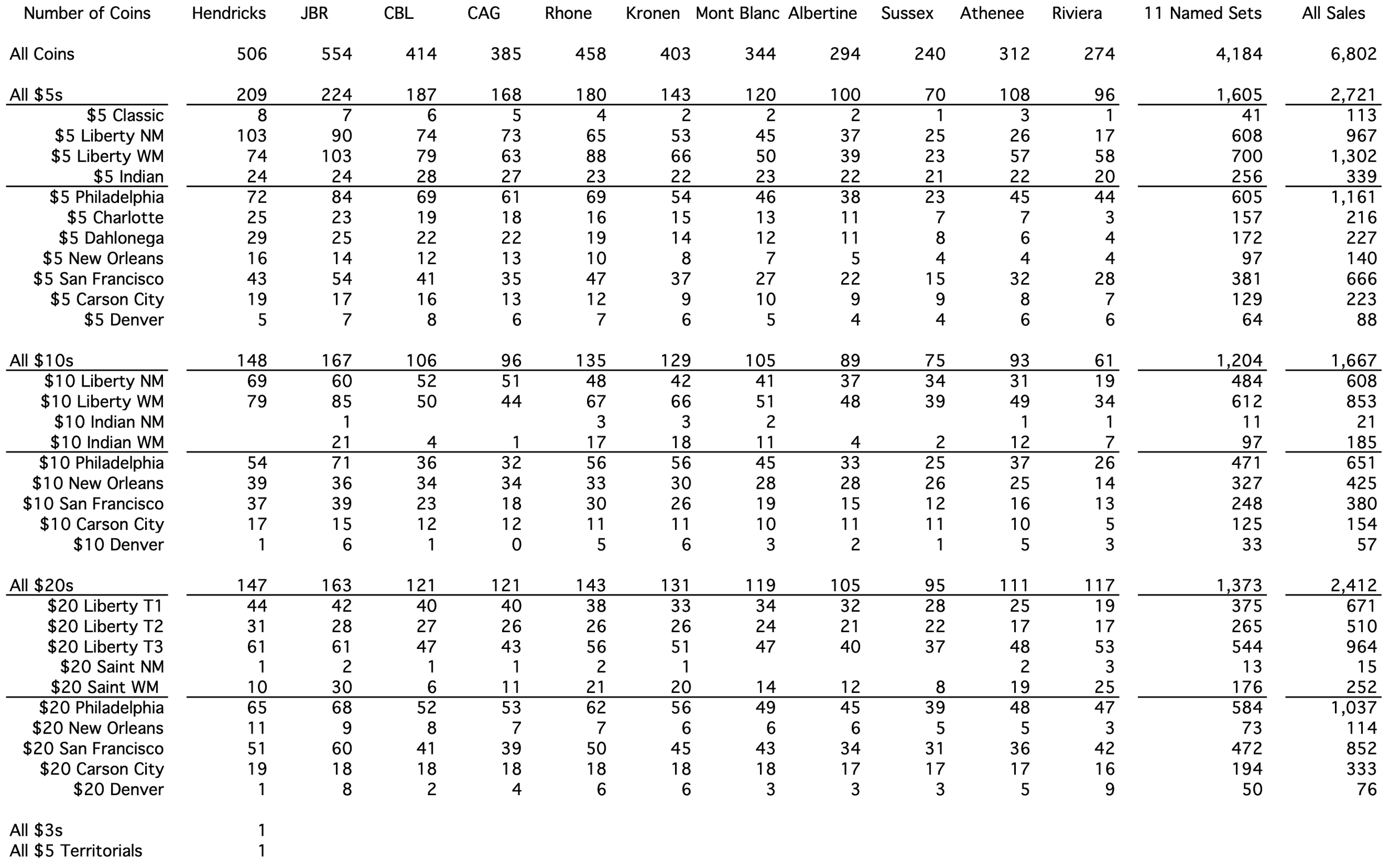

As mentioned at the outset of this article, there have been 29 SBG auctions that included at least 50 pedigreed Fairmonts. There have been thirteen Fairmont-only sessions, including the initial June, 2018, sale of double eagles, the August, 2020, sale of half eagles, and eleven named-set auctions that included half eagles, eagles, and double eagles.

The Fairmont sales appear to have violated one of the conventional norms of coin auctions, namely, that the best coins are sold first. It is now clear that the first of the eleven named-set sales, the so-called Hendricks Set auction of April, 2022, was the watershed event in the series of Fairmont sales, and contained the premier coins of the Fairmont Collection, in terms of both rarity and condition. The sales before and after the Hendricks Set auction were not its equals.

For example, the only 1870-CC $20 and the only 1875 $5 among the Fairmont coins were both in the Hendricks Set, and the auction prices realized (APRs) for these two coins were the two highest in the entire series of Fairmont sales, $810,000 and $480,000, respectively. Indeed, 17 of the 19 APRs over $100,000 from the entire series of Fairmont sales were for coins in the Hendricks Set.

A list of the data for the 19 top APRs is presented as the following table.

The entire series of Fairmont sales had a total APR of over $51.6 million. A detailed breakdown is shown as the following table, which has been broken into two parts for easier reading.

It should be noted that each named set sale tended to have fewer coins in lesser condition than its predecessors: thus, a direct comparison of the numbers is somewhat misleading. However, the overall features are clear: the eleven named set sales had over 80% of the total APR total from the Fairmont sales, and the Hendricks Set auction alone had over 26% of the total APR.

The following eye-chart presents the number of coins in the various sales. In terms of size, the JBR Set was actually larger than the Hendricks Set (and the largest overall), but only because the JBR Set contained a greater number of common-date coins. As the series of sales progressed, they became progressively smaller, largely because they contained fewer and fewer of the scarcer dates.

Names are rarely completely arbitrary, and I long wondered what the significance of the names selected for the Fairmont named sets might be. Then Doug pointed out that they are probably derived from the names of luxury hotels, mainly in Europe. His insight reinforces a suspicion that I have long harbored, namely, that the name “Fairmont” itself might refer to the chain of luxury hotels in Canada, since informed opinion (Rusty Goe, for example) seems to agree that the Fairmont hoard came from Canada – perhaps the marketing deal was negotiated at one of the Fairmont hotels (in Toronto or Montreal?). Unless SBG decides to tell us, we will probably never know for sure, but my hypothesis is perhaps as good as any.

Condition Statistics

An attentive reader has probably noticed that I have said relatively little up to this point about the condition of the Fairmont coins. This was not an oversight. Rather, it is because I have condition information mainly for the pedigreed Fairmonts, only, and the pedigreed Fairmonts are quite clearly the choicest from the hoard. Thus, for any subset of Fairmonts, I know the condition of the nicest coins, but not the typical condition. Accordingly, statements such as “The Fairmont coins tend to be very nice” are somewhat misleading. The statement: “The pedigreed Fairmonts sold in the SBG auctions tend to be very nice” is true, but not particularly informative, at least not about all the Fairmonts.

The exceptions to this are the Fairmont No-Motto $5s, for which I believe I have more-or-less complete condition information.

To substantiate the above points, I have analyzed condition information for three sets of No-Motto $5s, namely (1) All known Fairmont NM $5s, (2) All Fairmont NM $5s that have been sold in SBG auctions, and (3) All NM $5s that have been graded by PCGS, per the PCGS Population Reports of year-end 2024.

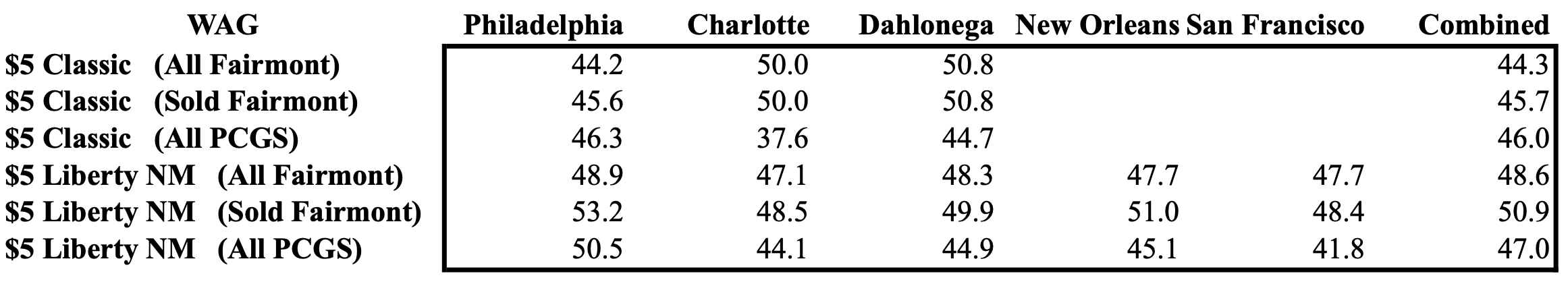

The following table presents a quantity that I call the WAG, which is the weighted average grade for all the coins with known PCGS numerical grades within a specified group. For example, the WAG for all $5 Liberty NM Fairmont coins is 48.6, i.e., between XF-45 and AU-50. There is, of course, no such thing as an XF-48.6 coin, but the WAG provides a handy quantitative way to intercompare groups.

Odds and Ends

The series of Fairmont sales has evidently concluded, not with a bang, but with a whimper. The Stack’s – Bowers Showcase Auction of April 2025 included a sequence of 72 fresh, pedigreed Fairmonts, all with PCGS-Details grades – truly, odds and ends from the inventory. However, I also believe it is likely that additional fresh, pedigreed Fairmonts will continue to appear occasionally in future SBG auctions.

However, the elephant in the room remains the enormous number of non-pedigreed Fairmonts, many of which I believe are still unsold today.

According to Yogi Berra: “It ain’t over ‘til it’s over.” I believe it’s not quite over, yet.